3.1. Basic Version Control¶

For code development, the history is of the same importance as the end results. As such we need a version control system (VCS) to help tracking the history. There are many VCS available, and here we will introduce one of the most powerful systems: Mercurial (hg, which is also used for the development of Python).

In this session, you will learn the basic of managing source code with the VCS tool Mercurial. We will cover the following topics:

When coming to this course, please prepare yourself a laptop with Internet connection, preferably running Ubuntu/Debian. If you are using Windows or Mac, you are on your own for installing required software.

3.1.1. Initialization¶

Mercurial is categorized as a decentralised VCS (DVCS). “Decentralised” means everyone in a collaborative team can maintain standalone development history, and synchronize it when necessary. The separation of tracking and synchronization makes the applications of the system broader than those of conventional centralised VCS.

3.1.1.1. Install¶

On a Debian/Ubuntu, the following command installs Mercurial for you:

$ sudo apt-get install mercurial

The command line hg should be available for you to use:

$ hg version

Mercurial Distributed SCM (version 2.2.2)

(see http://mercurial.selenic.com for more information)

Copyright (C) 2005-2012 Matt Mackall and others

This is free software; see the source for copying conditions. There is NO

warranty; not even for MERCHANTABILITY or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

Note

Because the command line is named hg, often we use it to refer to

Mercurial.

3.1.1.2. Configure¶

By default, Mercurial reads ~/.hgrc for configuration. Before any action,

we need to at least add the following setting into the configuration file:

1 2 | [ui]

username = Your Name <your@email.address>

|

Mercurial has to be told who is working on repositories, so that it can record correct information. Note the uesrname here is arbitrary. It doesn’t need to be the same as any of your local or online credential, but it’s good to set to a consistent value in all your environments.

In this course we also add the following setting:

1 2 | [diff]

git = True

|

to use the diff format that’s compatible to another popular VCS Git.

3.1.1.3. Initialize a New Repository¶

To this point we are ready to initialize our first Mercurial repository:

1 2 3 4 5 | $ hg init proj; ls -al

total 12

drwxrwxr-x 3 yungyuc yungyuc 4096 Jun 5 06:06 ./

drwxrwxr-x 7 yungyuc yungyuc 4096 Jun 5 06:06 ../

drwxrwxr-x 3 yungyuc yungyuc 4096 Jun 5 06:06 proj/

|

3.1.1.4. Repository File Layout¶

A repository is the database that Mercurial stores history to. In the

project we just created, the repository is in the subdirectory .hg/ of

proj/:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | $ ls -al proj/

total 12

drwxrwxr-x 3 yungyuc yungyuc 4096 Jun 5 06:06 ./

drwxrwxr-x 3 yungyuc yungyuc 4096 Jun 5 06:34 ../

drwxrwxr-x 3 yungyuc yungyuc 4096 Jun 5 06:06 .hg/

$ ls -al proj/.hg/

total 20

drwxrwxr-x 3 yungyuc yungyuc 4096 Jun 5 06:06 ./

drwxrwxr-x 3 yungyuc yungyuc 4096 Jun 5 06:06 ../

-rw-rw-r-- 1 yungyuc yungyuc 57 Jun 5 06:06 00changelog.i

-rw-rw-r-- 1 yungyuc yungyuc 33 Jun 5 06:06 requires

drwxrwxr-x 2 yungyuc yungyuc 4096 Jun 5 06:06 store/

|

As you can see, a Mercurial repository is nothing more than a directory named

.hg/ containing some data. Tracking (or managing) a software project with

Mercurial pretty much is changing the .hg/ directory, and we don’t do it

by hands, but by the convenient tools of Mercurial, specifically, the hg

command line.

3.1.2. Basic Concepts¶

There are some fundamental concepts we need to remember before using Mercurial:

- Working copy: it’s basically the working directory of everything are you tracking in the project.

- Changeset: the difference between two tracked revision of the working copy (directory).

- Repository: where we store the changesets.

3.1.2.1. Graph of Changes¶

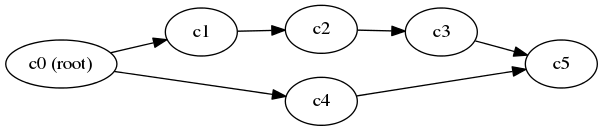

The following figure shows the graphical representation (directed acyclic graph, DAG) of a Mercurial repository:

Changesets in a repository¶

In the figure each node represents a changeset, and c0 is the root. Every repository can have one and only one root. Because the root is the first “change” in the repository, the repository we just initialized has no root:

1 2 3 | $ hg log

$ hg id

000000000000 tip

|

3.1.2.2. Using the Help System of Mercurial¶

As you can see, there’s nothing after hg log, and the “tip” id (the latest

changeset in a repository) is null. You can find more information about the

command by using hg help:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 | $ hg help log

hg log [OPTION]... [FILE]

aliases: history

show revision history of entire repository or files

Print the revision history of the specified files or the entire project.

If no revision range is specified, the default is "tip:0" unless --follow

is set, in which case the working directory parent is used as the starting

revision.

File history is shown without following rename or copy history of files.

Use -f/--follow with a filename to follow history across renames and

copies. --follow without a filename will only show ancestors or

descendants of the starting revision.

By default this command prints revision number and changeset id, tags,

non-trivial parents, user, date and time, and a summary for each commit.

When the -v/--verbose switch is used, the list of changed files and full

commit message are shown.

Note:

log -p/--patch may generate unexpected diff output for merge

changesets, as it will only compare the merge changeset against its

first parent. Also, only files different from BOTH parents will appear

in files:.

Note:

for performance reasons, log FILE may omit duplicate changes made on

branches and will not show deletions. To see all changes including

duplicates and deletions, use the --removed switch.

See "hg help dates" for a list of formats valid for -d/--date.

See "hg help revisions" and "hg help revsets" for more about specifying

revisions.

See "hg help templates" for more about pre-packaged styles and specifying

custom templates.

Returns 0 on success.

options:

-f --follow follow changeset history, or file history across

copies and renames

-d --date DATE show revisions matching date spec

-C --copies show copied files

-k --keyword TEXT [+] do case-insensitive search for a given text

-r --rev REV [+] show the specified revision or range

--removed include revisions where files were removed

-u --user USER [+] revisions committed by user

-b --branch BRANCH [+] show changesets within the given named branch

-P --prune REV [+] do not display revision or any of its ancestors

-p --patch show patch

-g --git use git extended diff format

-l --limit NUM limit number of changes displayed

-M --no-merges do not show merges

--stat output diffstat-style summary of changes

--style STYLE display using template map file

--template TEMPLATE display with template

-I --include PATTERN [+] include names matching the given patterns

-X --exclude PATTERN [+] exclude names matching the given patterns

--mq operate on patch repository

-G --graph show the revision DAG

[+] marked option can be specified multiple times

use "hg -v help log" to show more info

|

3.1.3. Commit¶

Let’s make the first commit:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | $ touch file_a

$ hg add file_a

$ hg ci -m "Initial commit."

$ hg log

changeset: 0:2fee2d78ec72

tag: tip

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sat Jun 15 20:52:23 2013 +0800

summary: Initial commit.

|

Mercurial command-line is very smart and knows how to shorthand commands. hg

ci is equivalent to hg commit. “Commit” means to “take the difference

between the current revision and the working copy and store the difference in

the repository as a new changeset”. Therefore after the commit you have a new

changeset. If you want to see what files are in each of the changesets, use

hg log --stat:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | $ hg log --stat

changeset: 0:2fee2d78ec72

tag: tip

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sat Jun 15 20:52:23 2013 +0800

summary: Initial commit.

file_a | 0

1 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

|

3.1.3.1. Adding New Files¶

When we make new files in the working copy, by default Mercurial doesn’t track them. For example, let’s make several empty files:

1 2 3 4 5 | $ touch file_b file_c file_d

$ hg ci -m "This commit won't work."

nothing changed

$ ls

file_a file_b file_c file_d

|

See? hg ci doesn’t allow us to commit a changeset because it thinks

“nothing changed”, but indeed there are three new files file_b, file_c,

and file_d. It becomes clear that Mercurial doesn’t “know” these new files

when we use the hg st (status) command:

1 2 3 4 | $ hg st

? file_b

? file_c

? file_d

|

The question marks (?) indicate those files are not tracked by Mercurial.

We need to hg add them:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 | $ hg add file_b file_c file_d

yungyuc@hayate:~/work/writing/pyengr/tmp/proj

$ hg st

A file_b

A file_c

A file_d

yungyuc@hayate:~/work/writing/pyengr/tmp/proj

$ hg ci -m "Add three more files."

$ hg log --stat

changeset: 1:7fb98d36f680

tag: tip

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:04:51 2013 +0800

summary: Add three more files.

file_b | 0

file_c | 0

file_d | 0

3 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

changeset: 0:2fee2d78ec72

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sat Jun 15 20:52:23 2013 +0800

summary: Initial commit.

file_a | 0

1 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

|

3.1.3.2. Modification of Files¶

Mercurial will detect the changed contents of tracked files. Let’s try it with some change:

1 | $ echo "Some texts." >> file_a

|

hg st knows file_a is changed (see the M in front of file_a):

1 2 | $ hg st

M file_a

|

And you can check the difference by hg diff:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | $ hg diff

diff --git a/file_a b/file_a

--- a/file_a

+++ b/file_a

@@ -0,0 +1,1 @@

+Some texts.

|

Finally we can commit:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 | $ hg ci -m "Change file_a."

$ hg log

changeset: 2:35f496a1ff0b

tag: tip

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:27:45 2013 +0800

summary: Change file_a.

changeset: 1:7fb98d36f680

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:04:51 2013 +0800

summary: Add three more files.

changeset: 0:2fee2d78ec72

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sat Jun 15 20:52:23 2013 +0800

summary: Initial commit.

|

3.1.3.3. The Simplest Work Flow¶

After learning to commit files, you basically can use Mercurial to track anything. The general procedure is:

- Initialize a repository by

hg init nameto start a project. - Create some blank files,

hg add file1 file2 ..., andhg ci -m "Commit log message." - Edit the files and

hg ci -m "Some meaningful commit logs."the changeset. - Continue with steps 1–3.

Mercurial discourages editing history, so even with some history-changing functionalities (like MQ), you cannot easily change what you’ve committed. Your repository is a pretty safe strongbox for your work.

3.1.4. Ignorance¶

When adding a bunch of files to a repository, sometimes we are lazy and do something like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 | $ touch file_1 file_2 file_3 file_4 generated

$ hg add

adding file_1

adding file_2

adding file_3

adding file_4

adding generated

$ hg st

A file_1

A file_2

A file_3

A file_4

A generated

|

Assume generated is a file generated form a script. We don’t want to track

it since it changes every time when we run the script. One way to do it is to

be explicit when adding:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | $ hg revert .

forgetting file_1

forgetting file_2

forgetting file_3

forgetting file_4

forgetting generated

$ hg add file_[1-4]

yungyuc@hayate:~/work/writing/pyengr/tmp/proj

$ hg st

A file_1

A file_2

A file_3

A file_4

? generated

|

It resolves the issue, but with two drawbacks:

- Now we can’t be lazy any more.

hg stsays it doesn’t know aboutgenerated, about which we don’t care.

Mercurial provides an ignore file to better solve this problem. Let’s add

.hgignore into the repository:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 | $ echo "syntax: glob

> generated" > .hgignore

$ hg st

A file_1

A file_2

A file_3

A file_4

? .hgignore

$ hg add .hgignore

$ hg st

A .hgignore

A file_1

A file_2

A file_3

A file_4

$ hg ci -m "Add ignorance." .hgignore

$ hg ci -m "Add 4 empty files."

$ hg log --stat -l 2

changeset: 4:06dacab043bf

tag: tip

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:47:18 2013 +0800

summary: Add 4 empty files.

file_1 | 0

file_2 | 0

file_3 | 0

file_4 | 0

4 files changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

changeset: 3:871d0c94b01e

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:47:02 2013 +0800

summary: Add ignorance.

.hgignore | 2 ++

1 files changed, 2 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

|

A real example of .hgignore can be found at

https://bitbucket.org/yungyuc/pyengr/src/tip/.hgignore.

3.1.5. Publish to Bitbucket¶

Bitbucket is a online hosting service for Mercurial (and Git, which I ignore here). We can push our local repository to Bitbucket (or BB in short) to make it available to the world (a public BB repository) or a selected group of people (a private BB repository).

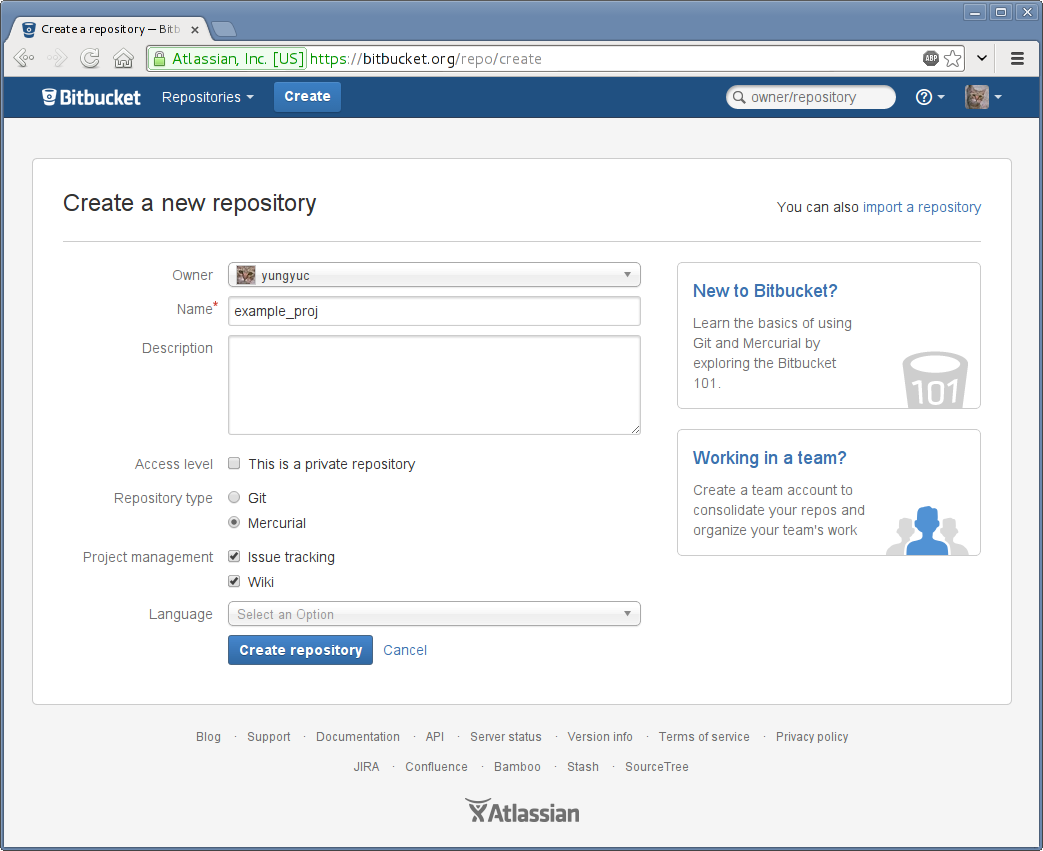

To proceed, you need an account at Bitbucket. It’s free. After having the account, you can create a repository:

Click the “Create repository” button and we are ready to go. If you have added your SSH key to BB, you can push your local changes to BB with it:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | $ hg push ssh://hg@bitbucket.org/yungyuc/example_proj

pushing to ssh://hg@bitbucket.org/yungyuc/example_proj

searching for changes

remote: adding changesets

remote: adding manifests

remote: adding file changes

remote: added 5 changesets with 10 changes to 9 files

|

Note

Of course you need to replace

ssh://hg@bitbucket.org/yungyuc/example_proj with the repository you

created. And if you haven’t set a SSH key at BB, you will need to use the

HTTP protocol to communicate with your BB repository:

https://username@bitbucket.org/username/example_proj (replace

username with your BB user name).

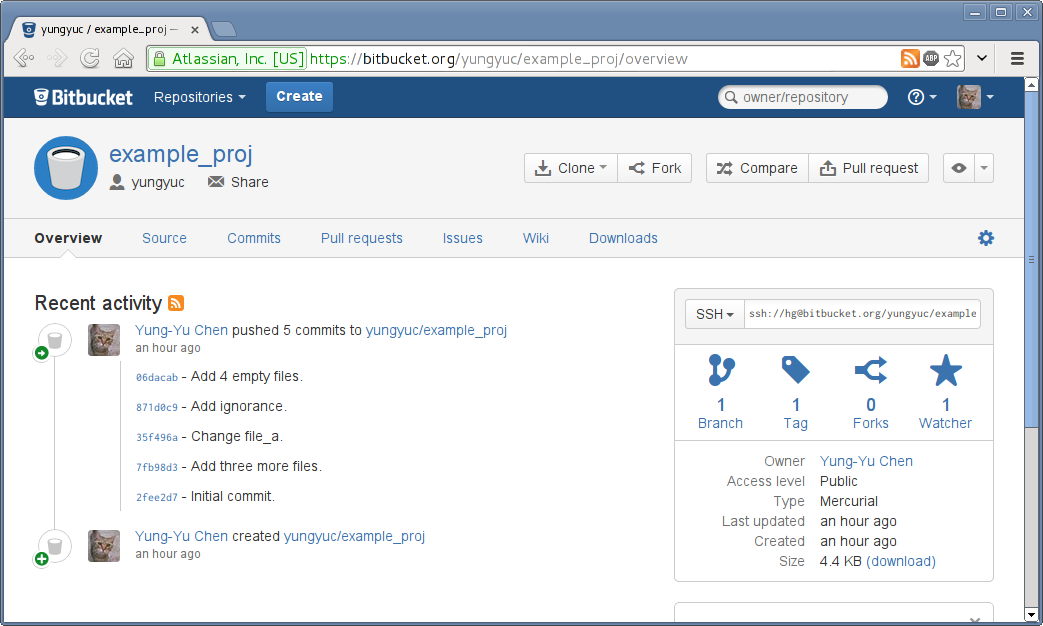

After pushing the changes, you should see the front page of your BB repository like:

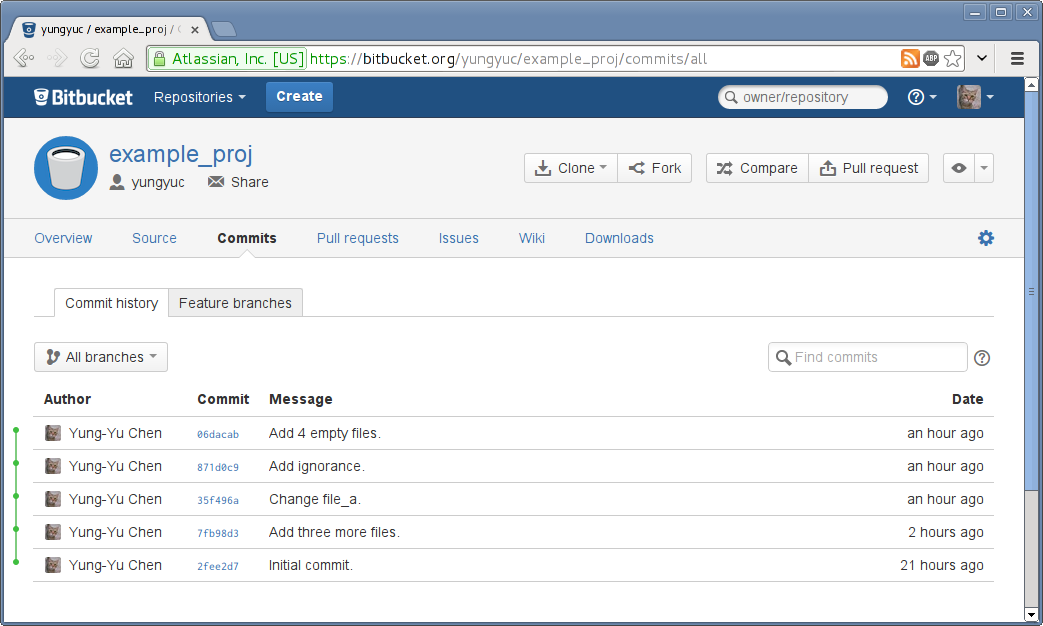

Clicking “Commits” will bring us to a page to view a graphical history of the commits:

Since we’ve made the BB repository public, everyone in the world can collaborate on it.

3.1.6. Mercurial Queue¶

Mercurial Queue is often called “mq”. mq is an important feature of Mercurial,

but it is implemented as an “extension”. To enable it, edit

your ~/.hgrc and add the following lines:

1 2 | [extensions]

hgext.mq=

|

Note that if there is already a section named [extensions], don’t repeat it

and just add the second line hgext.mq= to your setting file ~/.hgrc.

Mercurial queue is a tool for us to manage “patches”. The extension was inspired by quilt and seamlessly integrated into Mercurial. Because Mercurial discourage modification of history, mq is the answer for history-editing actions. Mercurial queue allows us to systematically change what has been committed into a repository, and we fully understand we are changing the history, because mq uses a different set of commands.

After enable the extension, you will have a bunch of new commands: qnew,

qref, qpush, qpop, qfin, and several others.

3.1.6.1. Create a Patch¶

Use hg qnew to create a new patch:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | $ hg qnew test -m "Patch for testing."

$ hg log -l 3

changeset: 5:860f045d5a1a

tag: qbase

tag: qtip

tag: test

tag: tip

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 23 18:00:30 2013 +0800

summary: Patch for testing.

changeset: 4:06dacab043bf

tag: qparent

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:47:18 2013 +0800

summary: Add 4 empty files.

changeset: 3:871d0c94b01e

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:47:02 2013 +0800

summary: Add ignorance.

|

The first argument after hg qnew command is the patch name. In this

example we created a patch named “test”. As we saw in the output of hg

log, a mq patch is nothing more than a regular changeset! But since it’s a

“patch”, there must be something distinguish it from a regular changeset, isn’t

it?

1 2 3 4 | $ cat .hg/patches/test

# HG changeset patch

# Parent 06dacab043bf1beb5d01f20c5d127341d980c4b8

Patch for testing.

|

Here’s the difference: mq maintains a directory .hg/patches for all patches

belonging to a “Mercurial queue”. Each patch is a file in the directory with

the file name set to the patch name.

When creating a new patch without any change in the working copy, you will get

an empty patch like the “test” patch we made. If we qnew a patch with

existing modification in the working copy, the modification will be

incorporated into the patch:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 | $ echo "some text" >> file_1

yungyuc@hayate:~/work/writing/pyengr/tmp/proj

$ hg qnew modify -m "Create a patch with some modification in working copy."

yungyuc@hayate:~/work/writing/pyengr/tmp/proj

$ hg qdiff

diff --git a/file_1 b/file_1

--- a/file_1

+++ b/file_1

@@ -0,0 +1,1 @@

+some text

$ hg log -l 4

changeset: 6:efbbac003006

tag: modify

tag: qtip

tag: tip

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 23 18:17:01 2013 +0800

summary: Create a patch with some modification in working copy.

changeset: 5:860f045d5a1a

tag: qbase

tag: test

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 23 18:00:30 2013 +0800

summary: Patch for testing.

changeset: 4:06dacab043bf

tag: qparent

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:47:18 2013 +0800

summary: Add 4 empty files.

changeset: 3:871d0c94b01e

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:47:02 2013 +0800

summary: Add ignorance.

|

3.1.6.2. Incremental Change¶

mq allows us to slowly cook a changeset, i.e., a patch. We can modify the

working copy bit by bit, and save the changes into the patch. At the beginning

only file_1 was changed:

1 2 3 | $ hg qdiff --stat

file_1 | 1 +

1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

|

Let’s make more change:

1 2 3 4 | $ echo "some other code" > file_3

$ hg diff --stat

file_3 | 1 +

1 files changed, 1 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

|

Use hg qref to “refresh” the patch. After the refreshment, the

modification is moved from the working copy to the patch:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | $ hg qref

$ hg diff --stat

$ hg qdiff --stat

file_1 | 1 +

file_3 | 1 +

2 files changed, 2 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

|

3.1.6.3. Popping and Pushing Patches¶

A committed changeset can’t be easily changed. In fact, it’s nearly impossible to do it without the mq extension in Mercurial. The “obvious” way to change history in Mercurial is mq.

Right now we have two patches applied in our repository:

1 2 3 | $ hg qapp

test

modify

|

The first applied patch is “test”, while the second is “modify”. Since they

are patches, we can unapply and reapply them. And we do that with hg qpop

and hg qpush commands, respectively.

Although it is Mercurial “queue”, it actually operates like a stack, and we can pop and push patches from and to a mq. Let’s pop the last patch for demonstration:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | $ hg qpop

popping modify

now at: test

$ hg qapp

test

$ hg log -l 2

changeset: 5:860f045d5a1a

tag: qbase

tag: qtip

tag: test

tag: tip

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 23 18:00:30 2013 +0800

summary: Patch for testing.

changeset: 4:06dacab043bf

tag: qparent

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:47:18 2013 +0800

summary: Add 4 empty files.

|

And then push it back:

1 2 3 | $ hg qpush

applying modify

now at: modify

|

We can also pop or push everything at once:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 | $ hg qpop -a

popping modify

popping test

patch queue now empty

$ hg qpush -a

applying test

patch test is empty

applying modify

now at: modify

$ hg qapp

test

modify

|

3.1.6.4. Finalization¶

After a series of hack, we will turn the patches in a mq back into regular

changesets. We will do it by using hg qfin command:

1 2 | $ hg qfin

abort: no revisions specified

|

One common mistake in using the command is forgetting to specify the patch to

finish. By default hg qfin doesn’t finish all patches, so that we can

selectively finish one:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | $ hg qser

test

modify

$ hg qfin test

$ hg qser

modify

|

Alternatively, we can also finish all patches at once:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | $ hg qfin -a

$ hg qser

$ hg log -l 3

changeset: 6:be3db2f671d5

tag: tip

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 23 18:33:01 2013 +0800

summary: Create a patch with some modification in working copy.

changeset: 5:4e435afd759f

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 23 18:25:29 2013 +0800

summary: Patch for testing.

changeset: 4:06dacab043bf

user: yungyuc <yyc@solvcon.net>

date: Sun Jun 16 16:47:18 2013 +0800

summary: Add 4 empty files.

|

Note that when a patch is applied in a repository, Mercurial won’t let you push, until now:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | $ hg push ssh://hg@bitbucket.org/yungyuc/example_proj

pushing to ssh://hg@bitbucket.org/yungyuc/example_proj

searching for changes

remote: adding changesets

remote: adding manifests

remote: adding file changes

remote: added 2 changesets with 2 changes to 2 files

|

3.1.7. Other Topics¶

This is a basic tutorial to version control and Mercurial. There are several important topics that we haven’t touched:

- Clone and pull.

- Branch (multiple heads) and merge.

- Tag.

- Multiple mq and mq repository.

We will visit them another time.